The air in the boardroom of the Restoration International Church headquarters was thick, not just with the humid afternoon heat of Accra, but with the heavy scent of “Anointing Oil” and the suffocating weight of judgement.

Outside, the distant honks of tro-tros and the faint cry of a plantain seller provided a rhythmic backdrop to the silence inside. Pastor Aka sat on a hard wooden chair, facing the “Trinity” of his undoing.

Pastor Aka sat on a chair that felt far too small for a man of his stature. Once the “Golden Boy” of the Konongo District, known for his resonant voice and ability to pray until the heavens seemed to crack open, he now looked like a man who had been caught in a tropical downpour without an umbrella. He had climbed the ranks through sheer charisma, but the same fire that fueled his sermons had led him into the warmth of another man’s home.

His relationship with the leaders had always been one of “Father and Son”—a precarious Ghanaian hierarchy where loyalty is the only currency. But today, the exchange rate had crashed.

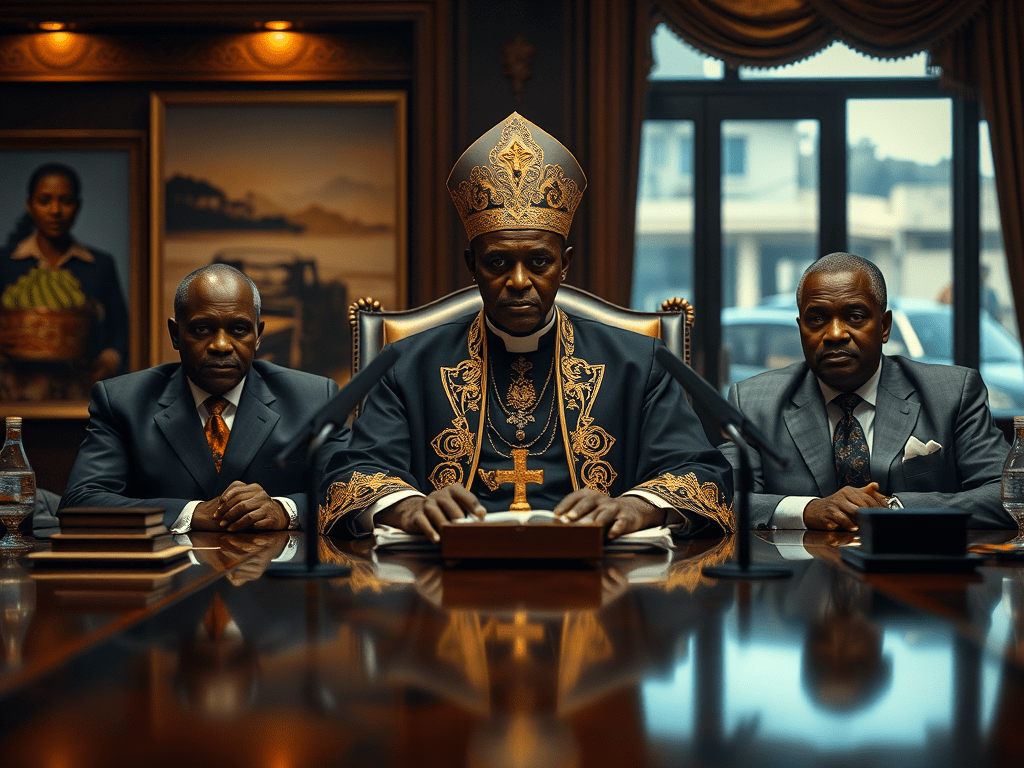

The High Table of Judgement

In the centre sat Archbishop Mandala, the General Overseer, looking regal in a bespoke suit that cost more than the annual tithes of a village branch. To his left was Pastor Bimpong, the Administrative Bishop, whose face was as stiff as his bleached collar. To the right sat Elder Mireku, a simple man whose only job was to represent the “sheep” of the congregation.

The crime was clear: Pastor Aka had been caught in an affair with a church member’s wife. In the world of Ghanaian ministry, this was the ultimate “offside” goal.

“Is it true?” the Archbishop thundered, his voice vibrating through the floorboards.

Pastor Aka looked down at his scuffed shoes. “It is true, Papa. I have failed the Lord, and I have failed the trust you put in me. I am ready for my cross.”

The Sentence

The scolding that followed was a masterclass in “holy” insults. Pastor Bimpong spent twenty minutes explaining how Aka’s “weak flesh” had dragged the church’s name through the gutters of Konongo.

The verdict was swift:

- One year suspension without a pesewa of pay.

- A total ban from the pulpit.

- A public apology to the congregation.

“You are a shepherd who ate his own sheep,” the Archbishop sneered, wiping sweat from his brow with a silk handkerchief. “Now, leave us before the wrath of God falls on this room.”

The Table Turns

Pastor Aka stood up, but he didn’t move toward the door. A strange, calm smile played on his lips—the kind of smile a man wears when he knows a secret that could stop a heart.

“Thank you, Archbishop,” Aka said softly. “But before I go to my exile, I have a few greetings to pass on.”

The room grew chillingly quiet.

“Archbishop,” Aka continued, his eyes locking onto the leader’s. “Do you remember a young lady called Esther? She lives in Darkuman Last Stop. She said she came to you for spiritual consultation during the ’21 Days of Fire’ fast. She said the consultation ended… quite intimately.”

The Archbishop’s hand, midway to his face, froze. “I… I don’t know what you are talking about. Who is Esther?”

Aka didn’t blink. He turned to Pastor Bimpong. “And Bishop, do you remember Maame Serwaa from Kasoa, Millennium City? She told me all about your ‘extra-curricular’ activities at the Star Hotel in Koforidua during the National Youth Conference.”

The Melting Point

The atmosphere shifted instantly. The “holy fire” in the room was replaced by a cold, psychological dread. Pastor Bimpong, usually a man of many words, suddenly looked like he had swallowed a bone. Beads of sweat—larger and more frantic than before—began to pour down the Archbishop’s face.

“Let us… let us pray,” the Archbishop stammered, his voice losing its thunder. “The meeting is over. We have reached a conclusion.”

“I don’t think we have,” Aka whispered, leaning over the mahogany table. “Because Esther is my cousin. And Maame Serwaa? She’s been my friend since secondary school. It seems we are all shepherds with a taste for the flock.”

Elder Mireku, the only one with a clean conscience, looked from left to right in total bewilderment. “What do we do now?” he whispered.

Aka didn’t answer. He simply reached into his pocket, pulled out a small pocket Bible, and placed it on the table. “Read Matthew 7:1-5,” he suggested. “The part about the plank in your own eye is particularly interesting.”

Without another word, he adjusted his jacket and walked out into the Accra sunshine.

Two weeks later, the congregation in Konongo was waiting for the news of their pastor’s official shaming. They expected a letter of dismissal. Instead, a memo arrived from the Headquarters.

“Due to his exceptional administrative skills, Pastor Aka has been promoted. He is hereby transferred from the Konongo District to the Osu District to serve as the Senior District Pastor.”

In the church world, moving from Konongo to Osu is like moving from a bicycle to a Bentley. It wasn’t a punishment; it was a reward for silence.

Pastor Aka sat in his new office in Osu, listening to the hum of the air conditioner. He wasn’t a hero, and he wasn’t a saint. He was simply a man who knew that in a house built of glass, the one who holds the biggest stone is the one who knows where everyone else is hiding.

Questions for Reflection:

- The Moral Dilemma: Is Pastor Aka’s promotion a victory for justice, or a deeper failure of the church’s integrity?

- The Mask of Leadership: Why do we often demand perfection from leaders while ignoring the “planks” in our own eyes?

- The Price of Silence: If you were Elder Mireku, would you have spoken up, or would you have stayed silent to protect the image of the institution?

Leave a comment