The Altar of Mammon: The Weight of an Envelope

The dust of Jinijini never truly settled; it simply hovered, a fine golden veil over the lives of those who tilled the earth. For Pastor Nyawuame, the District Pastor, that dust was a constant companion—on his shoes, in his throat, and settled deep within the creases of his worn Bible. Having served the Jinijini District of Restoration International Church for four years, he was a man who knew the geometry of hunger. He had four children and a wife whose grace was the only thing more resilient than their poverty. He hadn’t seen a full month’s salary in years, surviving instead on the “widow’s mite”—the gift of a tuber of yam here, a bag of maize there—offered by his impoverished congregation of farmers.

The atmosphere in January 2026 was heavy, not just with the harmattan haze, but with the solemnity of death. Pastor Amable, a retired and revered minister, had passed. The responsibility of his burial fell upon Nyawuame’s thin shoulders. But the burden wasn’t just the funeral; it was the “Protocol.”

The Arrival of the Giants

On January 9, the “Princes of the Church” arrived from the Headquarters in Accra. Archbishop Bimpong, a man whose presence was as heavy as his title; the Administrative Bishop, a silent shadow of authority; and Pastor Blewusa, the Chairperson of the Pastors’ Association, whose eyes were always searching for the bottom line.

They were chauffeured into Jinijini, their air-conditioned SUVs a stark contrast to the rusted bicycles of the locals. Nyawuame had secured rooms at the Abenase Guest House. It was clean and honest, but to men accustomed to five-star porcelain in Accra, it felt like a slight.

During the final preparatory meeting, Nyawuame’s heart hammered against his ribs. He looked at his elders—men with calloused hands and sun-darkened skin.

“We have done our best, Pastor,” the Head Elder whispered, patting a stack of envelopes. “The harvest was lean, but the people gave their hearts.”

The Transaction of Grace

The funeral on Saturday was a masterpiece of Ghanaian mourning—bittersweet and loud. But as the service ended and the leaders prepared to depart, the spiritual gave way to the temporal. The back of the Archbishop’s vehicle was groaning under the weight of “gifts”: sacks of garden eggs, crates of tomatoes, and yams so large they looked like carvings from the earth itself.

Pastor Blewusa pulled Nyawuame aside near the car, his voice a conspiratorial hiss. “How much is in each envelope, Nyawuame? Be quick.”

“The names are written on them, Brother,” Nyawuame replied, his voice steady despite the tremor in his hands. “Does the amount change the blessing?”

Blewusa’s face hardened. “Don’t be naive. The Archbishop’s honourarium should be no less than 1,500 Cedis. The Bishop, 1,000. Mine, 600. That is the standard.”

Nyawuame felt a flash of righteous heat. “Standard? I have not seen 1,000 Cedis in a single month for years. My children eat because of the yams in that boot, not because of a salary. We have given what we have. Does the Church not provide your travel per diem?”

Blewusa didn’t answer. He simply climbed into the front seat, his face a mask of indignation. Nyawuame handed over the four envelopes: Driver, Chairperson, Bishop, Archbishop. He waved them off with a smile that felt like a prayer for peace.

The Reckoning in the SUV

The silence inside the luxury SUV lasted only until they cleared the village outskirts. Then came the tearing of paper.

“Only 800?” the Archbishop bellowed, holding the notes as if they were soiled. “After a four-hour drive? Is this a joke?”

“I received 600, Your Grace,” the Bishop sighed, leaning back as if he had been physically struck.

“And 400 for me,” Blewusa muttered from the front.

The Archbishop’s face contorted with a cold, administrative fury. “He is disloyal. He is ungrateful. Blewusa, call that boy. Tell him he is to report to my office in Accra this Tuesday. I will not be insulted by a village priest.”

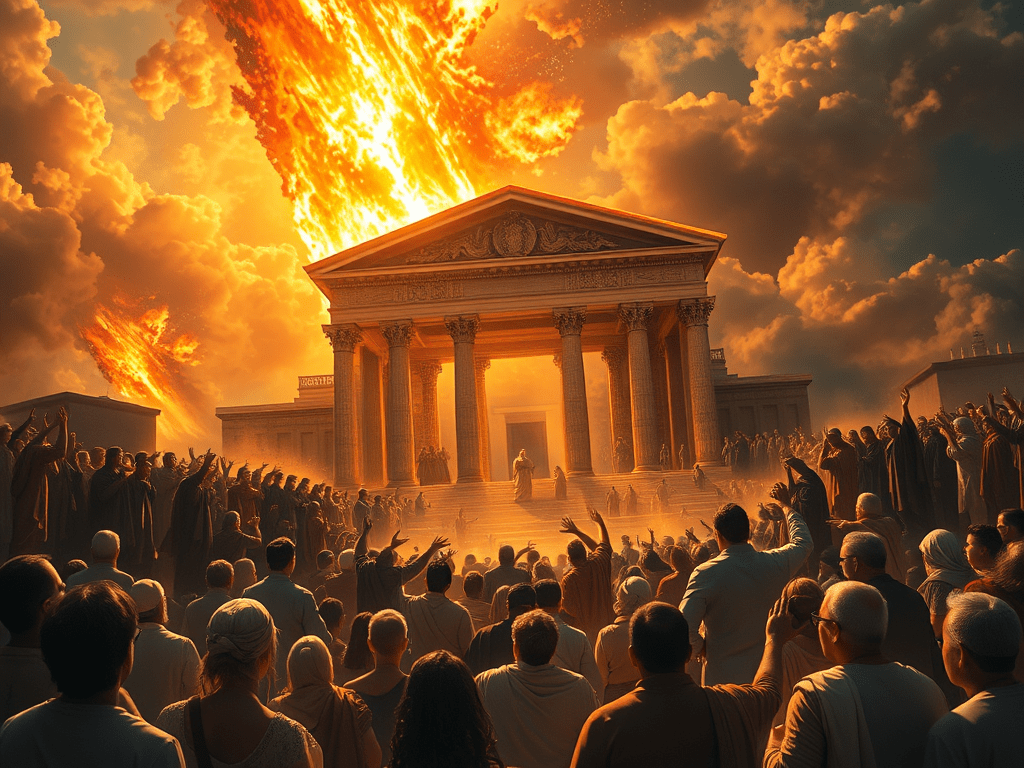

The Baptism of Fire

On Tuesday, Nyawuame stood in the plush, carpeted office at the Headquarters. He felt like a chick surrounded by hawks. The air-conditioning was freezing, but he was sweating. Elder Mireku, representing the laity, sat in the corner, his face unreadable.

The “Baptism of Fire” lasted an hour.

“You see this hamper?” The Archbishop pointed to a mountain of imported chocolates and fine wines in the corner. “Pastor Aka brought this from the Osu District. He knows how to honour the office. But you? You put us in a hovel. You gave us envelopes that are an insult to the calling.”

Nyawuame’s voice was a whisper. “The people of Jinijini are farmers, Your Grace. They gave their best…”

“I could have moved you to a prosperous district,” the Archbishop interrupted, his voice dropping to a dangerous purr. “But I see you are an enemy of the vision. I will teach you a lesson in humility.”

Nyawuame knelt. He apologised for a debt he did not owe. He wept for a church that had lost its way. He left the office with his head bowed, and a week later, his “punishment” arrived: a transfer to a remote, sun-scorched outpost in the farthest reaches of the north, a place where even the dust seemed to have died.

The Resurrection

The people of Jinijini did not take the news quietly. They saw the hollow eyes of their pastor and the arrogance of the Headquarters. They protested, but the “princes” were deaf.

Three months later, a new sign appeared in Jinijini: THE REDEEMER’S CHURCH.

Nyawuame didn’t have a grand building. He had a canopy and the love of a people who knew what it meant to be seen. Within a year, the pews of Restoration International were empty. The farmers took their tithes, their yams, and their devotion to the man who had suffered with them.

When the news reached Accra that the Jinijini branch—once a steady, if modest, contributor—had collapsed, the Archbishop panicking, sent a letter. It offered Nyawuame a “Lucrative Position” at the Headquarters, complete with a car and a bungalow.

Nyawuame read the letter standing in the middle of his bustling, vibrant new congregation. He thought of the weight of those envelopes and the weight of the tears he had shed on the Archbishop’s carpet.

He picked up a pen and wrote a single sentence in reply:

“The sheep have found their Shepherd; I suggest you find yours.”

Restoration International in Jinijini eventually became a warehouse for grain. The Altar of Mammon had finally crumbled under the weight of its own greed.

Reflective Questions

- On Leadership: Does the “honour” demanded by a leader carry more weight than the “sacrifice” offered by the led?

- On Institutionalism: When does a church stop being a sanctuary for the soul and start being a marketplace for the ego?

- On Integrity: If Pastor Nyawuame had borrowed money to fill those envelopes with the “required” amounts, would he have been a “good” pastor or a participant in a lie?

- On Justice: In your own life, have you ever mistaken someone’s humility for weakness, only to find that their resilience was your undoing?

Leave a reply to Anonymous Cancel reply